Restructuring in Rough Seas: An Overview of the Dynamics for Working Out Troubled Loans in an Uncertain Global Environment

By Steven T. Kargman

In the best of times, complex corporate debt restructurings can be a very challenging process. But in the current environment, in the midst of a global financial crisis and a slowdown in the global economy, such debt restructurings are likely to become even much more vexing. The global financial crisis will mean that companies in need of refinancing may not be able to find such financing, and this lack of financing could push certain companies into debt restructurings or insolvency proceedings. In the ensuing debt restructurings or insolvency proceedings, the parties may not be able to rely on readily available financing necessary to keep troubled or insolvent businesses operating. Moreover, the global economic slowdown may mean that there can be no short-term assurance of steady or strong demand for services and products provided by companies undergoing debt restructuring.

The shipping industry has not been immune from these forces buffeting the global financial and economic system. Over the past few years, the shipping industry has vastly increased its capacity, but in the current environment, this could make shipping companies vulnerable as demand for shipping capacity drops given falling economic activity around the globe. Also, in recent years, in order to finance the purchase of new vessels, the shipping industry has taken on large amounts of new debt. But how difficult will this new debt be to service in a seriously constrained economic and financial environment?

Continue Reading

Is Shipping Headed Towards a Restructuring Tsunami?

By Hamish Norton and Harold Malone, Jefferies & Company, Inc.

Financial conditions in the shipping industry have deteriorated significantly and are expected to result in broad-based financial restructuring activity. While each situation is unique, many companies are showing early warning signs that they may be entering the restructuring waters (see the table below for a list of some of these signs). Understanding the process and players is an important part of being a proactive restructuring participant. This article discusses the current market environment, provides an introduction to the restructuring process and addresses some possible outcomes.

It is a common misconception that the term “restructuring” is equivalent to bankruptcy. In truth, many restructurings are out-of-court, consensual processes that allow companies to stabilize their business, develop a strategic plan to restore profitability and right size their capital structure. An experienced restructuring advisor with in-depth industry understanding and the ability to access the capital markets can be critical to developing and implementing a solution that maximizes value for all stakeholders. Moreover, early action is key – engaging an advisor before the start of strategic discussions allows companies to evaluate a variety of alternatives that may not be available later in the process.

Continue Reading

The Role of the Flag Administration in Difficult Times

By Jorg Molzahn, and Brad Berman, Liberian International Shipping and Corporate Registry

The worldwide credit crunch has placed many burdens on shipowners and their financiers. And while no one wants to be perceived as “talking down” the market, it would be irresponsible for flag administrations not to be examining their obligation to assist.

Let’s begin with a short question and answer -

Has the Liberian Registry been approached to lay-up ships? Yes.

Have Recognized Organizations/Class Societies called to discuss withdrawal of class on ships free of recommendation for failure of an owner to pay outstanding fees? Yes – one.

Are any Liberian flag ships presently subject to arrest proceedings? Yes – Two.

Are nervous financiers calling to check on the status of their mortgages? Yes.

Has the Liberian Registry started to conduct seminars on ‘The Role of Flag in Difficult Times? Yes.

Continue Reading

Shipbuilding Contracts – how much “wiggle room” do buyers and their banks have?

By John Forrester, Partner, Holman Fenwick Willan

One of the key questions being asked by shipowners with newbuildings on order is to what extent they can legitimately walk away from those orders. For buyers who are unwise enough – or unfortunate enough – not to have their post-delivery financing in place, this will be motivated partly by the difficulty of raising that finance. But in most cases it will be driven by the fact that ship values have declined and that the buyer wants to avoid paying a contract price, which far exceeds the current market value.

Similar questions are being asked by banks who have agreed to provide construction finance to their customers. If pre-delivery instalments have already been financed by the buyer’s bank, can it somehow recover those amounts if the contract price now greatly exceeds the newbuilding’s value? Moreover, can it avoid having to finance any remaining instalments under the building contract in such circumstances?

Continue Reading

Managing Risk Management

By Mike Reardon, Vice President, IMAREX

With the unprecedented collapse of dry bulk rates over the past few months, we have seen increased inquiry from those looking to maximize their risk management capabilities. The two most common lines of questioning we have been receiving are centered on cleared trading and the use of options. We will address both of these concepts below in the FAQ format.

What has changed in the market that has caused people to review their risk management procedures? The simple, though unfortunate, answer is that dry bulk rates have plummeted. The extreme nature of the decline has created concern that some parties may not be able to pay what they owe. This counterparty concern doesn’t just apply to FFAs. It also applies to the physical market. When ships begin to get redelivered early, or when Charterers are unable to make hire payments on time, the potential for a ripple effect begins to work its way through the business.

Other than counterparty risk, what issues are facing the industry? Because the magnitude of the losses can be quite large, people have been asking if there is a way to hedge, but without facing unlimited downside, as they could face with simple FFAs. The use of options allows people to hedge in this manner. The price movement of options and FFAs are of course similar – as the price of the option depends on the price of the underlying FFA – but, with options, you can limit downside.

Sounds complicated. It can be as complicated as you want to make it, or as simple as you want to make it. Let’s start with the concept of cleared trading first. We can then move to options.

Continue Reading

Managing Liquidity & Financial Challenges in a Downturn

By Socrates Leptos-Bourgi, Partner, PricewaterhouseCoopers

There is little doubt that over the last few months our world has changed. As the US credit crisis has spread through the global banking system to the rest of the world, many years of relatively strong economic growth and booming world trade driven by the emerging economies have, rather abruptly, been replaced by an environment of poor liquidity, stagnant trading conditions and damaged consumer and investor confidence.

The impact on the shipping industry has been dramatic. While many anticipated that the buoyant shipping markets would not last forever, few expected the downturn to be as dramatic as it has been. Within weeks, daily hire rates barely meet daily operating costs, market values have dropped sharply, some charterers fail to meet their obligations, new orders at yards are being cancelled, yards are failing to deliver as planned, raising new finance is more difficult and more expensive and scrap values have decreased significantly. This caught most shipping companies and the other participants in the market unprepared for the new challenges ahead.

Yes, This Time it is Different

By Randee Day, Managing Director, Seabury Group

When I was first asked several months ago to write an article for the “Survival Edition” of Marine Money, an ominous storm was brewing over the horizon of the global shipping market. There was concern over frozen public equity and debt markets, increasing illiquidity within the international banking system, and a precipitous plummet in the Dry Baltic index. The rapid collapse of the global financial markets, and in-particular key measures of the health of the maritime community, led many to wrongly assume that the decline would be short lived–after all, Chinese growth was there to save us.

When Things Go Bad – A Practical and Personal Perspective

Introduction

With the exception of the recent foray into mortgage lending, banks, prior to making loans, historically performed a ritual called credit analysis to determine the borrower’s qualifications and eligibility for a loan. The criteria are best summarized by the “5 C’s of Credit,” which are described as follows:

• The most critical is capacity or the ability to repay the loan. The primary source of repayment is cash and the bank will consider the cash flow from the business, the timing of repayment and the probability of successful repayment from this source or other possible sources.

• Banks also assess how much capital, or money the borrower has invested in the business. This is money personally invested in the business from personal assets and which is at risk should the business fail. This is money subordinated to the loan.

• Collateral is additional security consisting of pledged assets. If the loan cannot be repaid through cash flow this becomes the alternative source of repayment. Generally collateral secures a guarantee.

• The overall economic environment as well as the general condition of the industry are also critical factors in the bank’s judgment as to whether to grant a loan. Condition also includes the purpose of the loan.

• While it is capacity, which repays the loan, the question of whether the loan gets repaid at all is dependent on character. Many lenders in fact consider this even more important than capacity. Capacity is out of a borrowers control whereas the borrower’s sense of obligation is not. In many respects it is character that will determine whether a loan is repaid when things go bad. Bad credit decisions can be overcome by character when both parties work towards repayment.

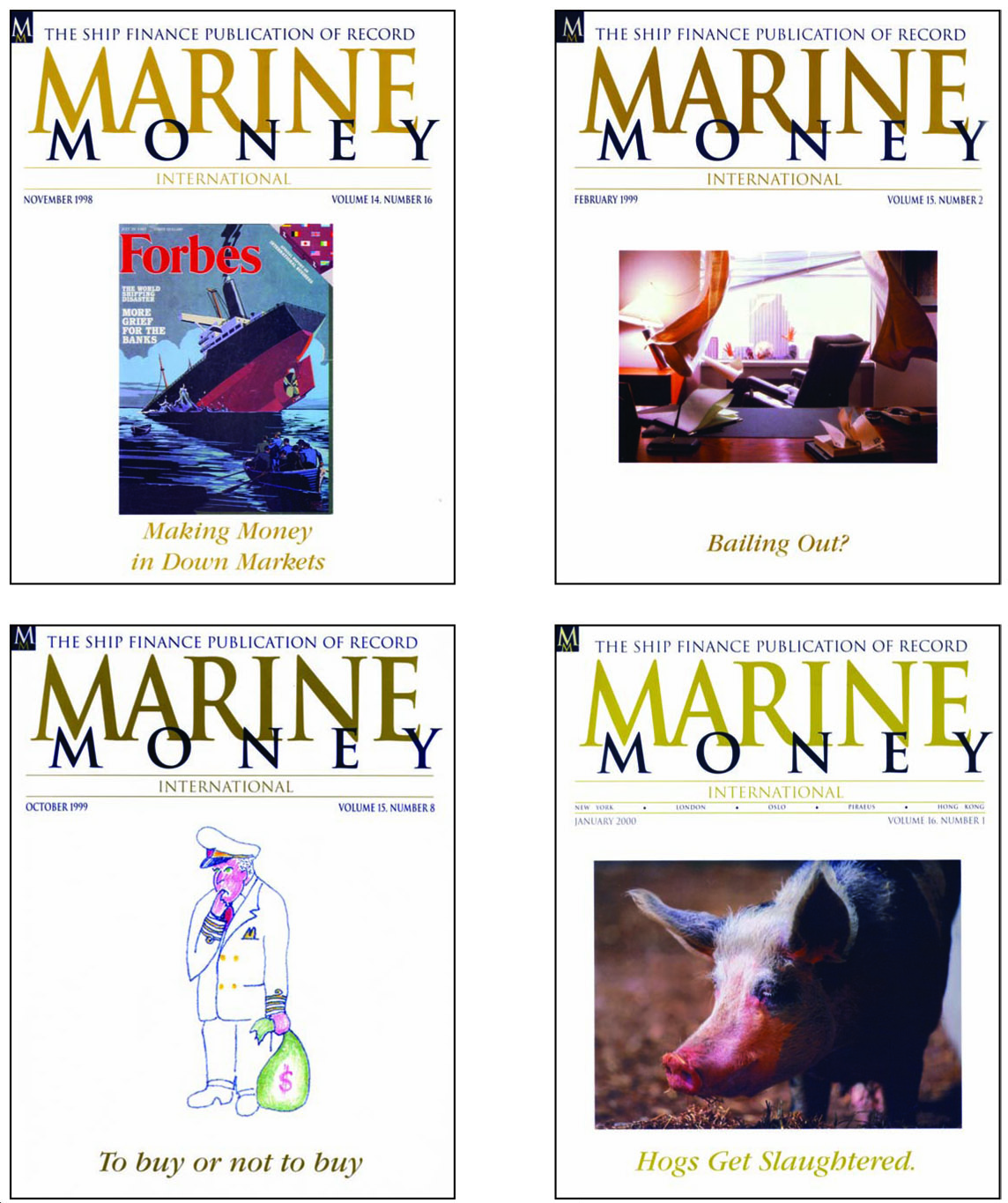

Scorecard

Having performed this ritual, the question to ask is how well did we do? The jury is still out and the full extent of the problem is largely unknown for the moment, although there are strong undercurrents that tell us all is not well. We may have forgotten about the cyclicality of the industry, but it did not forget us. The last time it caught us was in the late 1990s during the period of junk bonds. Did we learn the lessons from that experience? The simple answer is no. Cheap money, competitive pressures and a commodity bubble all conspired to blind us to the natural boom and bust of the shipping cycle.

Loans were made against record high asset values and gearing was beyond the norm. Offsetting this risk and giving comfort were long-term time charters. Most owners wisely opted to employ their fleet in this manner thereby creating extensive, visible and secure cash flows. However, reflecting the then current asset values these rates reached historic record levels. Although many were deemed first class, there was counterparty risk, some known and some not. Charterers included end users, typically viewed as less risky, while others chartered to operators, generally considered riskier. In this particular cycle, there was also a new phenomenon. With rates ever rising, charterers saw the opportunity of sub-chartering the vessel at ever-increasing rates and locking in their profit. This created a daisy chain of charters that collapsed with the first failure. Nonetheless, looking forward cash flows at the time, for a substantial percentage of the fleet, were locked in and secure. Or so we thought.

No one was quite ready for the perfect storm consisting of the collapse of the financial markets, recession and oversupply. Without delving into this well-known story, the effect was pitiless. Rates collapsed, however, values lagged supported by a lack of sales, either voluntary or involuntary, and the bundles of cash that had been earned over the last four years. The unwillingness of brokers to value assets was also supportive. For the moment, this cash, like the finger in the dike, is holding back what many consider the inevitable collapse of values bringing them in line with rates.

Unfortunately, the banks did not help themselves. Flush with liquidity, the banks competed heavily for deals and the owners, in the driver’s seat, pushed them to the limit. Spreads fell and covenants disappeared. But all this pales in comparison to the decision to forego principal repayment. Deals were struck with five years interest only. In some cases, reductions of availability under the facility took the place of actual loan repayments. Why not? The ships were all young and the market was strong and would stay so as the Chinese engine would run in perpetuity.

The decision to defer amortization was largely a consequence of the introduction of the high or full payout models based upon the MLP structure. With principal deferred, the amount of cash available to pay out as dividends was maximized. No cash was retained, with the understanding that growth would be financed. Unfortunately this requires unfettered access to both the equity and debt market. We learned too late that this model works for long-term stable businesses, like pipelines and not volatile businesses like shipping. As a consequence, shareholders got paid before the lenders. And the viability of this model, at least as it pertains to shipping, is in question.

Perhaps another flaw was a change in lending philosophy from the last crisis. Banks moved away from bilateral loans, with their emphasis on collateral, to a focus on corporate credits and balance sheet lending. This was a completely logical step. Lending on a single ship basis was more risky and did not lend itself to the possibilities of growth and fee income from the syndication of the large loans corporations required. There is also strength and diversity in numbers.

However, banks may have taken this form of lending to an extreme by doing it on an unsecured basis and relying instead on a negative pledge. Some of you may recall the junk bond era, where a borrower could forego giving security in exchange for paying an additional 12.5 to 25 bps on the rate. We do believe that no shipping loan should be unsecured. Quite simply the asset is another source of repayment, whether through sale or employment, should the borrower itself be unable to pay.

In contrast, balance sheet lending presupposes stability and the status quo. Accounting requires that assets be put on the balance sheet based upon historic value and then amortized based upon defined depreciable lives. Market value is of little consequence in the case of machinery in a factory. However, readily ascertainable market values in a cyclical market make balance sheets inherently unstable and subject to revaluation risk. As a consequence, balance sheets are not as rock solid as one might suppose. In the 1980s, there were, in fact, accountants who suggested replacing historic values with market values but this was rejected due to the subjective nature of valuing the assets as well as the fact that such financial statements would not be in conformance with GAAP.

As a consequence of high asset prices, deal size also became an issue in both nominal terms and exposure. Deal sizes in excess of $1 billion were not uncommon and hold pieces too were unexpectedly large as syndication dried up. Given the magnitude of the exposure, questions arose about the status of lenders’ shipping portfolios particularly in terms of risk and concentration. In fact, concerns about portfolio issues led DnB Nor to make a presentation on its shipping portfolio in December.

With hindsight, which as we all know is 20/20, the banks came up somewhat short as far as the “five Cs” were concerned. Capacity did not undergo stress testing to more normal historic levels. Capital remains at the mercy of asset values for the moment except in the case of the full payout model where the capital is long gone having been paid out as dividends. The only thing that can be said about conditions is that we were all blinded. On the positive side, the banks, which made secured loans, retain collateral although much of its value has been momentarily lost. Thankfully, character remains present and constant. And, as described in the beginning, it is the latter that will help solve the problem.

In all fairness, no one could have foreseen this perfect storm, which together with the speed of the collapse, make any criticism unwarranted. On the other hand, the banks did forget about risk when it came to pricing and, more importantly, in terms of structuring. By foregoing amortization in many cases, banks put their assets at risk and find themselves with highly leveraged underwater assets.

So what does all this mean? As a wise friend suggested values and rates have to find new levels. This implies the unthinkable in terms of what most thought were sacrosanct charters. Historically, no charterer except in a few minor instances failed in its obligation for to do so meant you were blacklisted and no one would charter a ship to you. For charterers to continue to meet their obligations is impossible today as contracted rates are so far beyond market it would bankrupt the charterer. Rates will have to be renegotiated to realistic levels with the logical quid pro quo being an extension of the charter at a reduced but reasonable rate. Although theoretically sound, the chasm between today’s rates and those of just a few months ago may prove difficult to bridge in reality. And the necessary fallout of that negotiation if successful is the concomitant restructuring of the loan or, if unsuccessful, possible foreclosure if the borrower cannot make the bank comfortable with its position.

Current State of Affairs

There is an old saw or truth about loan documentation. If the deal goes well, the documents remain on the shelf and collect dust. If both parties are cooperative, the old documentation is tossed and replaced with new. It is only when matters become litigious that anyone looks at the documents. Today we are certain of three things. Everyone is reviewing the mountains of paper that they signed at closing, there are lots of discussions taking place between lenders and borrowers and control has shifted back to the lenders. The workout process has begun.

Degree of Difficulty – Size Does Make a Difference

The success of the workout is largely dependent on knowledgeable parties working together to reach a common goal, specifically a workable repayment plan which takes into consideration the realities of the marketplace, while maintaining the collateral and meeting the divergent interests of the borrower and lender. The ability of the parties to accomplish this expeditiously may be impacted by the type of loan i.e. whether it is a bilateral loan, a club deal or a syndicated loan. On a scale of easy to difficult, it is easily recognizable that a bilateral loan, with two parties is much easier to deal with than a large syndicated loan with multiple parties. Although the documentation of the latter will delegate authority to the leads, there is still room for disagreement among the lender faction thereby delaying resolution. Given the involvement of relatively inexperienced lenders this is not a far-reaching scenario. The club deal falls somewhere in between as the club generally comprises a few banks all of whom are experienced in shipping. We recall with sheer amazement our first workout involving a drilling company where there were upwards of twenty lenders, represented by workout specialists, with no industry knowledge, sitting around a table demanding additional collateral. The discussions among the participants on this point lasted for hours until eventually we asked that our rig which was on lease to the borrower be redelivered to us against our release of any claim for the balance of the charter hire. The banks were happy to see us go but were no happier than we as we found a new home for the rig and quickly put it back to work.

The Evolution of the Workout

When problems begin to arise, the focus is initially on the loan agreement, which contains the financial covenants. With collapsing rates and declining values it is likely that one or more financial covenants have been breached requiring a waiver. These are easily granted but there is a price. Banks may seize this opportunity to improve their position. For example, the bank will likely restrict dividends and future investments, tighten covenants and ask for additional security or, alternatively a pay down of the debt. It is also not unheard of for the banks to extract a fee, increase the spread, add a cash recapture clause and terminate future commitments. As the loan now has achieved notoriety by appearing on the watch list, the banks de facto begin to have a strong influence on the management of the company.

While these discussions are taking place, it also behooves the bank to simultaneously focus in on the collateral and in particular the mortgage covenants. Cash flow is likely below breakeven levels and is being subsidized out of cash reserves or borrowings under existing facilities. This creates a myriad of problems made worse by the banks control of the freight account and its demand that it be paid. A cash shortage implies greater use of trade credit and therefore the potential for liens. Crew wages and insurance premiums may go unpaid and maintenance will likely be deferred. All of these actions diminish the value of the collateral. Liens and crew wages are valid claims against the vessel. Left unpaid they might lead to the vessel’s arrest by creditors or a visit by the ITF in support of the crew. The loss of insurance puts the collateral at risk and precludes the payment of claims while deferred maintenance may lead to expensive repairs. With the borrower illiquid, it is the mortgagee who foots all of these bills. Lenders need to closely monitor and independently verify, to the extent possible, the condition of their collateral.

The inability to make scheduled payments is a critical event both in terms of the lender/borrower relationship as well as its implications for treatment within the bank. This failure requires the bank to restructure the loan if there is “good character” and foreclosure if not. Restructuring generally involves the rescheduling of payments; most often accomplished by extending the term, and may include interest only with the quid pro quo being a cash recapture clause. Here too the bank may seek its pound of flesh including adjustments to economics and collateral demands.

Whereas the covenant default puts the asset on the watch list, a payment default requires more drastic action, as the loan falls into the non-performing category, which may include setting reserves or write downs if in fact the asset value has been impaired. These actions are risk and accounting driven. Payment of interest at a minimum is essential to avoid being classified as a non-earning asset.

The Last Resort

Presuming the re-structuring fails, the bank may have no choice but to foreclose on the collateral. In many respects this is a doomsday scenario whether cooperative or adversarial. No one wins, as there is no question that the asset has more value in the borrower’s hands. Once the step is taken the asset is immediately written down to its current value and of far greater concern is the fact that the bank, as mortgagee, assumes financial responsibility.

The first step in the process is to arrest the vessel in a favorable jurisdiction. The latter is generally defined as a country that has an extant body of maritime law including procedures for arrest. Taking legal advice is critical. The choice may make the difference between an expeditious process and one that can go on interminably. In addition, the jurisdiction will determine the priority of your claim on the vessel and whether intervening liens may prime, or come before, the mortgage.

The vessel can then either be sold privately or put through an auction process, with the latter being preferred as the vessel is cleansed of all liens. At the auction, the bank generally bids its note. Once control of the asset is awarded to the mortgagee by the court, which is generally the case, the bank is quite anxious to get it off its balance sheet mainly for liability reasons. In the hands of the bank, the asset is also worth less and so there is little incentive to sell. The solution for the bank is either to engage a workout specialist, such as Fairwind, Sunscot or Quantum, a professional ship manager, or just a friendly client to assist. As a first step, the bank will sell the asset to the party on a non-recourse basis simultaneously providing financing through a “soft” loan. A soft loan is one that is repaid strictly from the vessel’s earnings on a pay as you go basis. The “ friendly borrower” will normally be compensated through commissions on sale and purchase and chartering as well as management fees. There is also generally a residual sharing agreement with the profits beyond an agreed amount, generally less than the full exposure but more than the written down value, being shared. The goal of this exercise is to have an attractive operating asset which when the market inevitably turns can be sold and a recovery made. A recent example of a friendly transfer was the sale by Nordea of some of Britannia Bulk’s vessels to D/S Norden.

Tale of Four Foreclosures

To highlight some of the issues involved, we provide some examples, both good and bad, from our prior life. Generally as high-spread lenders, we dealt in many instances with second-tier owners. Most, it turned out were of “good character” but when things turned difficult in the late 1990s, some turned into pirates and scoundrels. We also erred in thinking that low cost older ships were less risky. That simply is not the case, particularly in a bad market where they are more often than not unemployable. The vessels described below were mainly built in the late 1970s and were more or less 20 years old at the time. In the instances described below, we retained Sunscot and Co. Ltd to assist us.

In one instance, we re-financed a 2,823 DWT Ro-Ro as a singleton for an owner. The market collapsed and employment opportunities in the Caribbean, where it traded, were non-existent. Payables ballooned as the vessel was in virtual lay-up. Then the P&I club struck. It raised premiums by 110% and made supplemental calls for the prior two years. In this instance the owner cooperated and the vessel was brought to the Bahamas where it was foreclosed in December 1999 and auctioned in February 2000. The vessel was subsequently sold to Tsakos with delivery in Miami. Today, she is still trading under the name “Platense.”

Another small Ro-Ro was financed against a charter with a substantial Panamanian operator. When the charter failed, the vessel was arrested by a third party creditor in Panama also in December 1999 and because of the established maritime law there, the vessel was quickly auctioned on February 1, 2000. Sunscot’s crew rebuilt both engines and then operated the vessel for a period carrying buses and cars out of Miami and Port Everglades. Eventually, the vessel got a cargo to Port Sudan and from there went to Alang where she was scrapped.

Despite a difficult start, one transaction that worked out very well involved a 12,625 DWT multipurpose vessel, which was on its way to Germany carrying ammunition. Due to disagreements among the investors, the owner tried to arrest the vessel in France. However, because of the cargo, the port authority refused it entry and it made its way to its original destination, Bremen, where the cargo was discharged. The vessel was arrested in November 1998. Since it lacks an established maritime code, Germany is not a favorable jurisdiction and the process dragged on. Among the delays was the requirement that the service of judgment to CT Corporation be made through diplomatic channels. Eventually, an auction took place in October 1999 nearly a year later. The result was astounding as we were outbid by B. Navi, who subsequently sailed the vessel to Latvia to pass special survey, which had expired during the arrest. Not only did the proceeds cover the costs for crew and lay-up, the bank made a substantial recovery. Part of the successful result was attributable to Sunscot’s replacing a mixed and unhappy crew with a working crew, which made necessary repairs and improved the cosmetic appearance of the vessel while the vessel was under arrest. Today the vessel is trading under North Korean Flag as the Gumbong.

As an interesting side note, we did make an unusual insurance recovery with respect to that same vessel. In November 1998, the owners made a claim against their hull policy for engine damage in the amount of $425 thousand. In September 1999, the claim was rejected by adjusters who argued that there were inherent problems with the engine and that the damage was not attributable to normal wear and tear. Rather than pursue the claim in court, which would have been extremely costly, we successfully made a claim under our mortgagee’s interest policy that was paid in December.

The final instance involved another tweendecker managed in the U.S. and on charter to a U.S based charterer. The charterer declared the vessel unseaworthy and cancelled the charter and as payments were not received we sought to arrest the vessel. The ship was foreign registered and had been instructed by the borrower to sail to the U.S. in order to make matters more difficult for the mortgagee. Under U.S. law, all claims by U.S creditors whether against the ship or the company would prime the foreign mortgage. Given the litigious nature of creditors in the U.S., we were certain everyone involved with the borrower would make claims against the vessel. If the vessel had gone to the U.S. not only would we have lost time, we suspect we would have lost a great deal of value. Fortunately, the crew had not been paid and we were able to convince them to disobey the owner and sail for the Bahamas where the vessel was arrested and our mortgage maintained its priority. After the auction, the vessel sailed to Bombay where she was scrapped.

As Al Yudes of Watson Farley & Williams describes it, the main lesson to be learned when it comes to arresting a vessel is “location, location, location.” Ideally, as Keith Martin of Sunscot suggests the ideal place to arrest is a port that applies the jurisdiction of English Law (Hong Kong, Singapore, Gibralter, Bahamas, and the U.K.). These are ports where the mortgagee’s position is really best protected and where the process of a court auction is well defined and procedures are well known and adhered to.

Finally, Mr. Martin notes a dramatic change from the 1990s when Russian, Burmese and Chinese crews just entered the foreign flag market and were not sure of their rights under maritime law. In today’s wired world knowledge is omnipresent and communication unfettered aided by the readily available cell phone. We know the ITF and other seaman’s societies are actively looking for unpaid crew and willing to help them. What is unknown is how today’s knowledgable crews will respond to an arrest.

Too Big to Fail?

Given the magnitude of the exposure, particularly on the dry side, there is the potential for a huge problem the likes of which we have never seen. Moreover, the financial system is already under great stress, which precludes much optionality. Nevertheless, we are certain that there is little interest on the part of the banks in exercising their rights and taking control of assets with the ensuing writedowns. Instead, we expect that the banks behind closed doors will be encouraging industry consolidation, along the lines of the tanker market, thereby creating fewer and stronger creditworthy dry bulk shipping companies which will be the survivors of this collapse.

If in fact that is the case this“… is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”1 Nothing would please us more.

So…

So….” sighed an exhausted Michael Parker as he ran his fingers through a mane of largely intact hair.

He punctuated the brief, but expansive, two-letter word by resting his chin in the cupped palm of his hand and then resting his elbow on the white tablecloth that covered the dais at the Intercontinental Hotel in London.

Was he vanquished? Was he asleep? Was he imitating Rodin’s famous thinker? Or was Michael’s neck simply too damned tired to hold up the weight of his highly active cranium?

“What have we learned?” he finally asked into the microphone and then exhaled so loudly through flaring nostrils that this observer could not help but imagine the equine events of which the Chairman was so, perhaps unnaturally, fond. Grey suits shuffled, eyes darted, but not a sound was heard among the crowd.