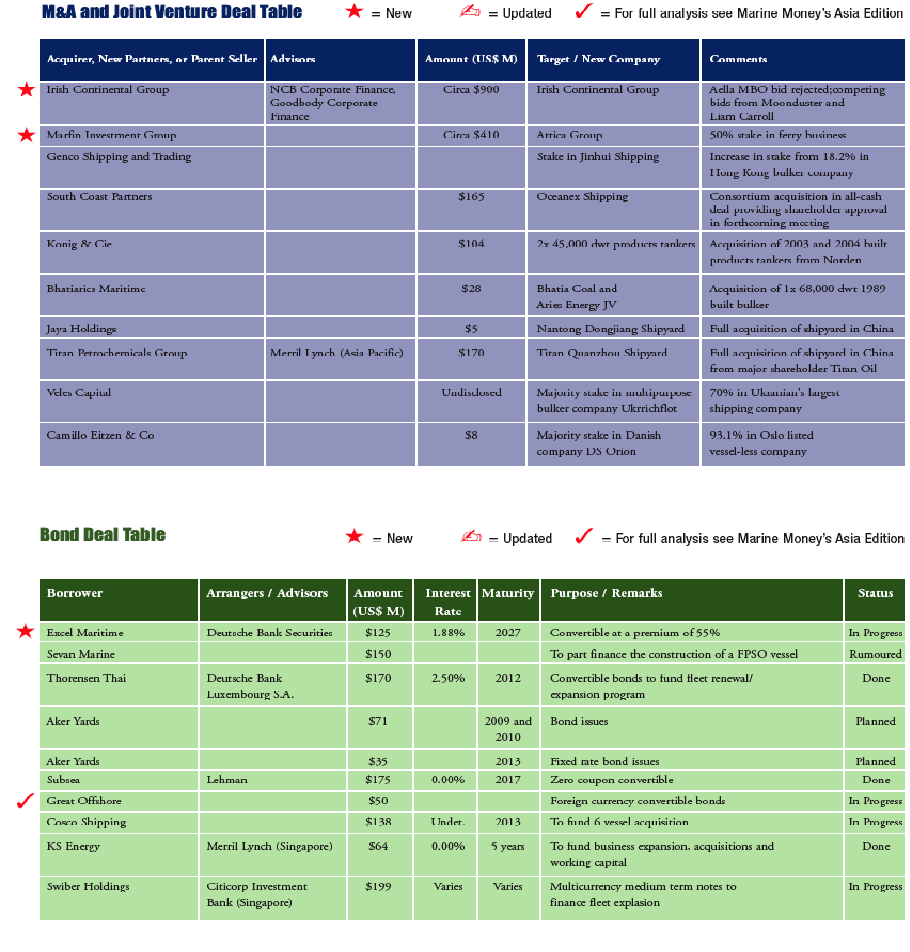

The Week in Review – 10/04/2007

Deutsche Sole Book on Extraordinary Excel Maritime Convertible Bond Issuance

Deutsche Bank Securities successfully sole managed yesterday’s extraordinary Excel Maritime convertible senior notes transaction. This is a very important transaction for ship owners, public owners particularly, coming as it does in the midst of continuing bank liquidity uncertainty caused by the US sub prime credit crunch. At a time when syndicated loans are struggling to find participants, and some banks have completely halted new business due to marginal funding cost increases or are offering new loans but only at much higher rates, Excel Maritime has secured $125 million (potentially up to $150 million if the $25 million greenshoe is exercised) that will pay interest semiannually at a rate of 1.875% per year. The convertible notes are due 2027, are non-callable by the company for seven years and are puttable by investors back to the company in years 7, 10 and 15. Continue Reading

Re-Rankings

Due to an unfortunate omission, which would have been nearly impossible for us to uncover, our 2006 Rankings of Shipping Companies as they appeared in our June/July 2007 issue were in error due to a single miscalculation.

Beginning in early May 2007, we began the process of collecting and inputting data into our rankings model. From each company’s annual report, there were multitudes of inputs to extract and then we sourced Bloomberg for historical foreign exchange rates and stock prices. This was done this year for 86 companies and, as you can imagine, presents quite a challenge. Continue Reading

Basel II and Residual Value Risk

By Howard A. Chickering

The new capital charges proposed by The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS or “Basel Committee”) of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in the framework of the Basel II Accord Rules (the “Basel II Rules”) are risk weighted and provide substantial relief for better rated credits. However, the Basel II Rules maintain a 100% weighting on operating lease residual values, which is highly penalizing for the leasing industry. This paper discusses the capital charge relief that can be provided to a bank subject to the EU’s Capital Requirements Directive by a residual value insurance policy provided by an insurer rated AA. Continue Reading

Financing with the Maritime Administration’s Capital Construction Fund

By H. Clayton Cook, Seward & Kissel

Background

In Europe and the United States the past half dozen years have born increasing witness to highway traffic congestion concerns and to the use of water transportation as a possible supplement and alternative. The U.S. Maritime Administrator speaks of the need to access “America’s Marine Highways.” However, the means for financing the vessels necessary to access this alternative have remained uncertain. Congress is now moving to make the existing Maritime Administration (“MARAD”) financing guarantee and tax deferral programs available for these America’s Marine Highways vessel financings. Continue Reading

Ireland as a Headquarter Location for Shipping Groups

By P. J. Henehan, Ernst & Young

The Irish government has been proactive in its aim to develop the shipping/shipping services sector in Ireland. Ireland’s young educated work force and enviable geographical location, together with the low level of corporation tax, have helped position the country as an attractive location to base shipping activities. Unlike other low tax jurisdictions, Ireland benefits from ever improving infrastructure, with six major ports located around the country. Recent developments including the adoption of a competitive Tonnage Tax regime have greatly enhanced Ireland’s attractiveness. Continue Reading

OSG’s Double Hull Tankers: Preserving Capital, Securing Optionality

By Matt McCleery

The most recent shipping IPO to debut in New York is the long-rumored OSG sale/leaseback Double Hull Tankers. As most readers of these pages know, OSG has been using the current strong tanker market and the company’s platinum credit standing to sell off select tonnage at high prices and lease it back at favorable rates for medium term periods.

These transactions allow OSG to take the capital gains as operating income and then continue to generate earnings by operating the ships. But more importantly, these deals allow OSG to control the intensity and profile of their asset ownership without losing control of the ships. In addition to selling ships and leasing them back, OSG has been actively chartering-in ships to achieve many of the same objectives. Continue Reading

THE IRISH SHIPPING MARKET

By Helen Noble, Mason Hayes+Curran

General overview of shipping market in Ireland

It is now almost seven years since the Irish Maritime Development Office, commonly referred to as the “IMDO” was established.1 Under the remit of the Marine Institute (a state Agency responsible for the research potential of Ireland’s marine resources), it was in its own words, Ireland’s first national dedicated development, promotional and marketing agency for the shipping services sector.

The IMDO has a statutory mandate to promote the growth of Irish Shipping and related services and to attract to Ireland marine related service sector operations along with key players in International Shipping and ancillary services. The mandate includes: Continue Reading

Greek Shipping Finance 2005 –Analysis and Trends, The Future of the Small Greek Owner And the Attitude of Banks

By Ted Petropoulos, MD, Petrofin S.A.

The Shipping Market and Banks

Both international and Greek shipping finance had over the 12 months from September 2004 to September 2005 to deal with an extremely turbulent shipping market. In the first six months up to April 2005, both newbuilding and secondhand vessel values as well as freight rates rose to unprecedented heights in shipping history across all sectors. Whereas banks welcomed the positive effects this boom brought to their customers and indirectly to their own shipping loan portfolios in terms of enhanced client liquidity, high asset values and cash flows, profitable vessel sales, and income security via period charters at high rates, they also became extremely wary of the market collapse that might follow.

As vessel values rose steeply, banks grew uncomfortable with lending a high percent age of finance that would result in historically very high loans per vessel. Where there were period charters with a high earnings stream, banks reduced the risk to a large extent by front-loading the loan repayment schedule so as to stay in reasonable touch with historical values and earnings at the end of such charters. Client pressure, and fierce competition between banks meant that high loan to asset financings had to be provided even in the absence of period charters. Banks in such cases tried to latch on to other client securities, but bank, however, competition also frustrated them from doing this in many cases.

Banks took comfort from their clients’ enhanced liquidity and fleet cash flows, but these often were not tied into the banks’ collateral packages, leaving banks to rely on their overall bankclient relationship to justify the enhanced levels of risk. Alternatively, banks had to assume that future earnings levels would be at higher average levels than before in order to justify the higher loans and loan residuals.

While happy to be lending for such modern vessels, it was a challenge for banks to meet the enormous rise of interest by Greek owners in newbuildings. This resulted in the need for banks to cope with high loan to value newbuilding client demand for many vessels that often either had no period charter cover or were to be delivered in future years when shipping conditions could not be forecasted with confidence. As newbuilding prices rose by approximately 60% between October 2003 and Spring 2005 (Clarkson’s Shipping Intelligence), banks began to feel relatively exposed when also committing to a 15-year payout loan profile. The Greek rush for newbuildings and modern secondhand vessels necessitated that banks maintain a flexible and competitive approach so as to maintain their client base whilst anticipating and building in safety features in the form of financial covenants and front-loaded loan repayments. On the whole, banks were successful in keeping client and loan risk within acceptable levels, resulting in most banks continuing to grow their loan portfolios and in some cases expanding their client base (see later).

The intense competition between banks focused primarily on the top tier clients who often took advantage of banks’ appetite to obtain both better loan terms and lower spreads.

Declining loan spreads did cause banks difficulties. Banks dealt with this in three ways. Firstly, by reevaluating Greek shipping risk. The younger age of collateral vessels and client fleets, their often enhanced employment position, better asset quality and maintenance, higher standards of management, transparency and information flow as well as the robust performance of Greek shipping over the last five years factored through each bank’s credit risk assessment models and allowed for lower spreads on account of higher credit ratings.

Secondly, many banks experienced a significant percentage of loan pre-payments, which were replaced with new fee generating loans that boosted loan portfolio yields, as well as higher loan commitment fees from newbuilding finance involving future vessel deliveries.

Thirdly, banks strove to enhance their non-risk products and services such as private banking, hedging services, advisory services and the like, which were in increasing demand by their increasingly liquid clients.

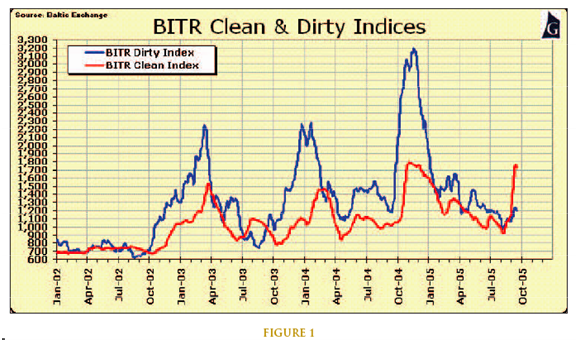

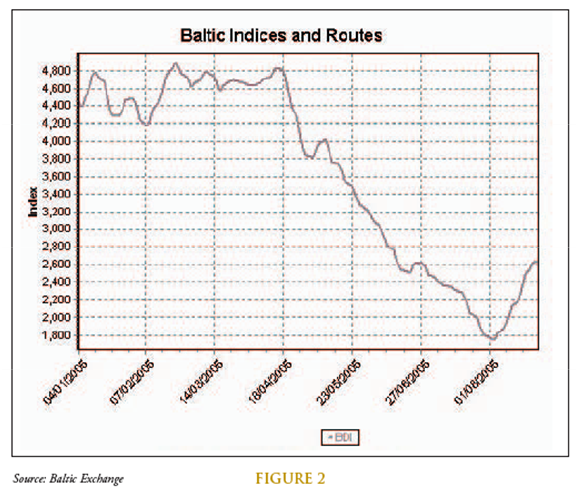

The shipping scene changed from April to September 2005 as a result of a pronounced fall in freight rates. As Figure 1 shows, the BDI fell from 4627 on 1st April 2005 to 1769 on 4th August 2005. Similarly, Figure 2 shows how the BITR fell from its December 2004 peak to very low levels by late summer 2005. Despite the severity of the fall, sellers of vessels refused to let go of their recent memories of high markets. Consequently, sellers were unwilling to sell vessels at prices corresponding to the low freight rates, whilst buyers maintained their buying interest. As a result, vessel values fell relatively little, only about 15% on average.

Banks reacted to the market falls with increasing caution and apprehension. Bank attention shifted to monitoring charterers’ performance for signs of the market bottoming out. Transaction flow reduced as the number of fresh newbuilding orders and secondhand transactions slowed. Banks, too, watched for signs of a slow down in the international economy, as a result primarily of the very large oil price increases up to the $70 per barrel level, which can be expected to undermine international growth.

So far, however, there have been few charterer failures. Client liquidity remains high, as do income flows from profitable charters secured in higher markets, which has protected clients and banks alike. The slowdown in shiplending activity have, however, been compensated to some extent by the pronounced IPO activity, especially strong up to the summer. Banks were called to provide standby facilities after successful IPOs, which allowed them to extend large well-structured facilities, keeping their overall loan numbers growing (see later).

With IPO activity slowing down as a result of the market correction, concerns about the price of oil, and a possible slowdown in international trade, banks became wary of new loans in the absence of secure employment. It is important to note that the prevailing freight rates do not support the current high values of vessels.

Rising bank lending statistics

As relatively short-term loans were replaced with relatively long-term loans to finance newbuildings and young vessels, the average repayment profile of banks’ loan portfolios became much longer. In addition, each bank’s average loan per client rose substantially over the last couple of years, due to higher asset values and the high number of newbuildings that were financed. On the whole, banks responded positively and energetically to the challenges and opportunities offered by booming market conditions, and the rush for newbuildings resulted in increased ship finance activities across the board. Consequently, basic loan volume growth slowed down over the last few months as banks and owners alike bid their time and awaited the new direction of the shipping markets. Let us now look into the development of banks engaged in Greek shipfinance using the Petrofin Bank Research© that was published earlier this year.

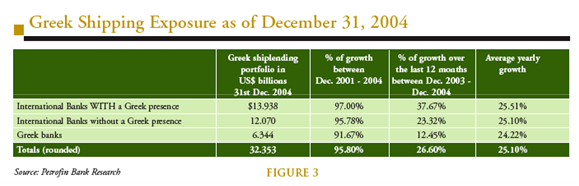

This research takes an annual snapshot of Greek ship finance, whereby all loan portfolios directed to Greek shipping are obtained from banks involved in the Greek market. Bank exposure as of 31st December 2004 is shown in Figure 3.

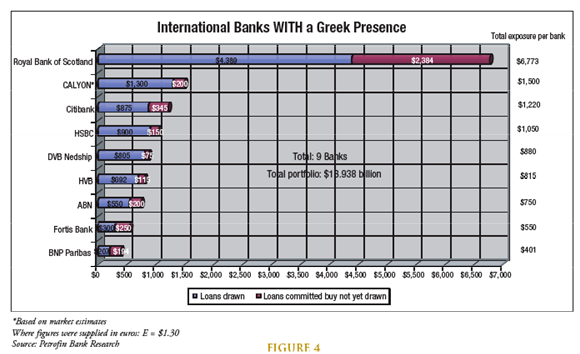

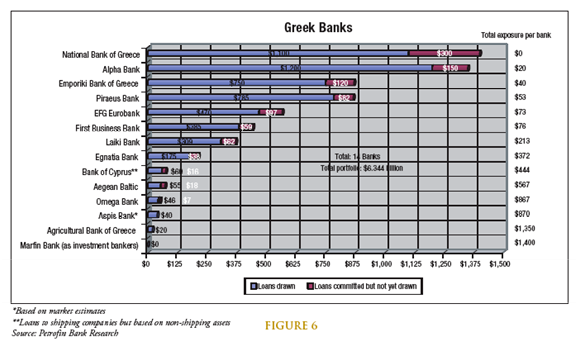

We note that the overall exposure to Greek shipping is $32.353 billion. Figures 4, 5 and 6 show the specific banks involved.

These banks have shown consistent growth throughout the last four years. Number one in Greek ship finance over all categories remains the Royal Bank of Scotland, which has shown an average yearly growth of approximately 37.59%. The overall category has shown an average percentage growth of 25.51% per annum.

International banks without a Greek presence, shown in Figure 5, showed an impressive increase in Greek shiplending during the last year from $9,787.73 million to $12,070.13 million, i.e. an increase of $2.282 billion or 23.32%. This increase reflects lending based on newbuilding and secondhand vessel prices in the current climate.

International banks that are not represented in Greece are showing an ever-growing interest in the Greek shipping market.

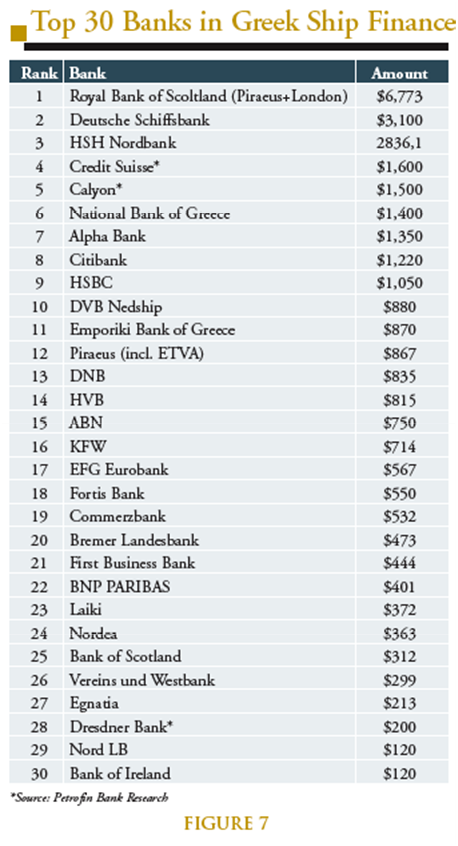

Greek bank exposure has been steadily increasing since December 2001, when our research was first published. Since then, the funds available to Greek shipping rose by over 90%. We note that Greek banks have become fully established in the sector. Figure 7 shows that as of last year, there were eight Greek banks ranking within the top 30 in Greek ship finance. It is important to observe that in this market of huge volumes and huge numbers, Greek banks have retained their competitiveness and are competing for Greek business on an equal footing with other international banks.

Greek ship finance has attracted the attention of the international business community for its returns and steady growth in the last years. As a result, all three categories of banks grew substantially last year, with non-Greek banks growing faster than Greek banks.

In view, however, of the drop in freight rates and slowdown in lending, it will be interesting to obtain the figures for 31st December 2005 and study the impact of this peculiar market, where vessel values are still high but employment security is at very precarious levels.

Capital Markets

Another key feature of Greek shipping that has had a significant impact on banks was the increasing appetite by Greek owners for tapping the international capital markets, in particular the U.S. Going public meant that such companies ceased to be private and rather secretive organizations, developing instead into corporations with full transparency and international management styles and organization. Overall, transportation IPOs, as a percentage of total IPOs, have shown remarkable growth since 1999, leaping from 0% for 1999 and 2000 to 2% in 2001, to 6% in 2002 and 2003, down to 3% in 2004 and then jumping up to 12% in 2005 (source: Renaissance Capital’s IPOhome.com). In the 12 months between May 2004 and May 2005, approximately $1 billion was tapped from the U.S. capital markets by Greek companies alone (source Lloyd’s Shipping Economist, June 05). Over the last six months, total international shipping IPOs amount to $2.212 billion, with Greek shipping IPOs representing almost 40% of those (source: Renaissance Capital’s IPOhome.com). Our estimate for 2005 is approximately $4 billion, subject of course to last quarter prevailing conditions.

Initially, such capital raising exercises resulted in early repayments of bank loans. However, soon thereafter fleet bank facilities, such as Diana Shipping’s $230 million facility with RBS were negotiated. This gave Greek shipping banks an opportunity to compete for much larger and more structured loan facilities than before. Interestingly, the much larger amounts did not seem to bother banks, who often competed to provide the whole or large chunks of such loans. New public companies often became the best clients for hedging and advisory services. Indeed, more banks engaged in Greek ship finance became familiar with dealing with corporate types than before, a crucial market development with long lasting implications.

Currently, there are over a dozen potential Greek IPOs in line for conclusion in the very near future. Should the shipping market remain dull and freight rates low compared with high asset values, the prospects for many IPOs are bleak. They will face a decision to either proceed on less attractive terms or to abort / temporize the issue for a better time later. In addition, the international investment climate is undergoing some turbulence on account of the high price of oil, which undermines the investor confidence that is so crucial to the success of IPOs. The game, however, is far from over, as there is an enormous potential pentup demand for IPOs by Greek shipping companies who see the public markets as their passport to growth and long term survival and success.

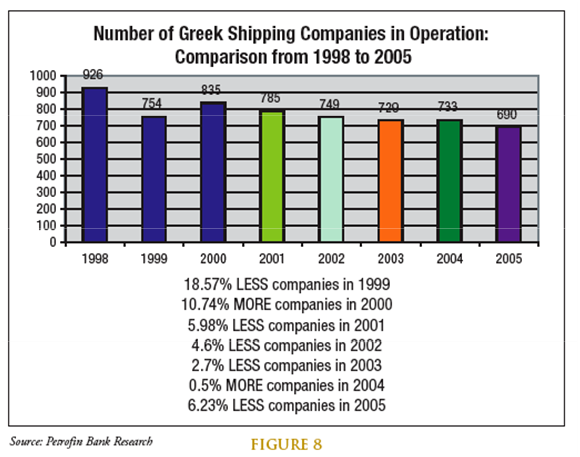

The Greek small owner and ship finance

The trend towards consolidation continued over the last year. Petrofin Research© published in April 2005 showed that the overall number of Greek companies fell from 733 in 2004 to 690 in 2005, as shown in Figure 8, whilst overall tonnage (in DWT terms) for vessels over 10.000DAT each controlled by Greeks fell from 180.3 million metric tons DWT to 173.3 million metric tons DWT. The age profile is also improving year by year, with the most notable improvement in the Greek tanker fleet, where the average age fell from 17.1 to 15.7 years.

Whereas the overall Greek controlled fleet shows a trend towards fewer but larger fleets, in line with international shipping trends, the smaller Greek owners with fleets of up to four vessels declined from 680 companies in 1998 to 445 in 2005, a loss of 34.6% over the last eight years. Many smaller Greek owners took advantage of the high vessel values to exit the industry at a profit, whereas others managed to grow their fleets and shift up to a larger category. Although there are always newcomers, the barriers to entry have risen and shipping nowadays requires high amounts of capital even for a new entrant.

In addition, it is true for shipping, even more than for other industries, that there exist significant economies of scale. Some of the main benefits include:

• Lower operating costs per vessel

• Enhanced fleet flexibility, efficiency and spreading of shipping risk

• Lower insurance, crewing and technical management costs

• Operating and technical economies of scale

• Lower capital costs

• More investment options available as a result of higher capital resources

• Enhanced ability to tap the international equity markets

• Greater viability of investing in a substantial infrastructure to meet the shipping challenges, as well as the ever-increasing regulatory restrictions

• Greater chartering flexibility and ability to attract charterers’ attention

• Ability to attract and keep a higher quality of personnel and professional managers.

In addition to these, one of the main benefits for larger owners is that of finance and the attitude of banks. Simply put, banks prefer larger owners, and they express this preference by providing such owners with higher percentages of finance, lower costs (spread and fees) and better terms. While there are a number of small owners with a proven track record with banks, a high quality of management and operations, enhanced technical ability, good liquidity and attractive fleet profiles, due to size, their names are still not on the banks’ target lists, which primarily consist of the largest (quality) shipping companies.

The main reasons for banks’ choices are a) banks believe that smaller owners represent a higher risk, and b) banks (having grown themselves) are more interested in sizeable clients with whom to develop sizeable loan business as well as to market their increasingly sophisticated products and services.

Moreover, as banks developed their credit evaluation models in accordance with Basel II, smaller owners fare less well under these models in risk assessment terms. Consequently, banks either prefer not to lend to such smaller owners or to do so by charging a much higher level of spread and fees to compensate for their perceived higher risk.

The ability to obtain finance in the first place and to do so efficiently and inexpensively is one of the main motivations for growth by shipping companies and at the same time the biggest difficulty for small owners.

Small owners tend to be primarily family owned businesses. Often there is a lack of clear succession, which may result in an owner leaving the industry. Many times the exit decision is the result of a prolonged shipping slump in which a small owner operating overage vessels cannot survive or the result of a high market where it is attractive for an owner to leave with high profits from the sale of his last vessels.

Although these market related reasons do affect owners, as has been evidenced by pronounced mobility at times of boom and recession, small owners wishing to stay in the industry have demonstrated the ability to do so by their sheer persistence. In addition, small owners running overage vessels often have no or little bank debt. As such, their survival depends on their ability to simply earn sufficient cash flow to cover their vessel operating costs, something they can do at almost all times.

Worth singling out are the increasing regulatory constraints that require a higher level of expertise and a greater dedication of human resources of all shipping companies, something that small owners cannot easily afford. The above increasingly regulatory environment has also affected the legendary benefits of flexibility enjoyed by the small owner that have been one of his main counter strengths.

Whereas a small owner can take investment and operating decisions more quickly, his ‘breathing’ room has reduced dramatically over the years. It is difficult to make quick decisions and be flexible when there are so many regulatory and other limitations affecting every decision.

Where small Greek owners excel is in their ability to spot an opportunity and move quickly. In addition, their all-round character, ability and aptitude towards shipping and its challenges represent substantial strengths.

Small owners often portray a deeper sense of commitment. The sheer character and doggedness of small owners often results in their enhanced ability to survive. The owner’s continuous presence in the company results in more effective per- Source: Petrofin Bank Research sonal attention and control, a more motivated workforce, closer operations and maintenance of vessels, closer relationships with charterers, bankers, suppliers etc. and a more focused and dedicated approach.

However, despite the importance of the above compensating factors, the market, bank and cost pressure towards larger size is relentless and increasing.

Contribution of Small Greek Owners to Greek Shipping

In addition to making up nearly two thirds of the market participants and controlling a large number of vessels, the presence of small owners adds depth, variety, individuality and character to Greek shipping.

Each owner seeks to identify and develop his own niche and owning / operating style. In so doing, small owners stress and rely on these factors as opposed to the sheer weight of numbers.

As to the question of whether there is still a viable market for small owners, the answer is undoubtedly yes. Small owners are flexible enough to be at the right place at the right time and to work a trade route that perhaps would not be of interest to a larger company. Even in a ‘difficult market’ like Europe, full Mediterranean/Black Sea, smaller owners have been well established for a long time now, especially in the field of short sea shipping. Owners with few but larger vessels trading spot as opposed to being fixed on long term charters have also the flexibility of positioning and negotiation.

Let us also not forget that Greek shipping supports an enormous number of providers of shipping goods and services of all sizes, nationalities and styles.

These providers enjoy developing close relationships with owners as well as catering their products and services to the individual needs of their specific clients. Often, these providers can also charge a little more for providing such services or by providing longer credit, which is of valuable assistance to small owners.

The presence of smaller owners has facilitated the emergence, especially in recent years, of banks specifically catering to the smaller owner. Without smaller owners, such banks, not surprisingly mostly smaller banks, would not have been able to compete with the enormously powerful global banks to provide loans and services to owners.

Small owners have also sought to adapt to the challenges of an increasingly difficult shipping environment by standing out with respect to others via superior quality, enhanced organizational skills and the development of their distinct strengths to enhance their competitiveness.

In addition, as Greek shipping stands out against other industries as a successful, rewarding and challenging industry, it has attracted an increasing share of young, educated and capable men and women. These people often make up for their lack of hands-on experience by their appetite, attitude and willingness to adopt new techniques and modern methods. Moreover, as they develop into decision makers in their own companies, they are more prepared to consider commercial alliances, mergers and acquisitions, going public to tap the international capital markets and developing their companies from family based to corporate. The success of Greek shipping has been primarily due to the commitment and skills of small owners who initially ventured into shipping to seek their fortunes.

They often came from within the ranks of shipping as such, being ex-captains or engineers or at times merchants and traders. Now small owners are joined by young, educated, capable and ambitious new owners who have selected shipping as the industry offering them the most attractive risk/reward profile. All owners are highly motivated, seeking success and the opportunity to grow rich and famous. Many are inspired by names of near mythical proportions such as Onassis and Livanos, whose ‘rags to riches’ stories have fuelled imaginations. Recently, the market took note of a similar success by Evangelos Pistiolis’ Top Tankers, which achieved fame and a large fleet by exploiting the U.S. capital markets.

It is true to say, therefore, that a number of today’s small owners will develop into tomorrow’s leading owners. This opportunity, prospect and challenge assists the Greek shipping industry not only to develop, evolve and grow but also to attract the human and capital resources that are essential to its future success.

The Future of Small Greek Owners

Readers should be wary of misinterpretation of the decline in the absolute and relative number of small Greek owners as a percentage of the total. The decline in numbers is a natural process, taking place internationally as part of the consolidation of ownership of international shipping and its concentration into fewer but larger global players.

However, the remaining (surviving) small owners are often stronger and better prepared to meet the challenges of modern shipping. In addition, realising that their small size works against them, they seek to compete in different ways, e.g. quality, market niche, differentiation, etc. Furthermore, more and more small owners are committed to growth and are seeking opportunities to do so. These opportunities are inherent in shipping via its market cycles, which allow small owners to develop a profitable investment strategy. Recently, there were additional opportunities in attracting fresh capital either via the public markets or by attracting private equity.

Even traditional family-run and self-supporting small Greek owners have a future and the opportunity to survive, strengthen and grow. Whilst their numbers may continue to decline in absolute terms, their overall presence and significance will continue to form the bedrock of Greek shipping and one of its important differentiating characteristics versus other nationalities.

The future of Greek ship finance

It is undoubtedly true that Greek ship finance has matured and is now one of the largest such markets in the world, both in terms of loan volume and the number and diversity of banks. The strength and evolution of the Greek fleet have been very important to the successful development of Greek ship finance. The recent trend towards newbuildings, younger fleets, better maintained vessels, public market activities, corporatisation, transparency and organizational efficiencies have all contributed to making Greek ship finance a lower risk proposition. What is more, this quality leap is far from over as there is still a great deal of potential for improvement.

Although loan spreads and overall yields have declined, the risk reward ratio is still positive and attractive to banks.

It is our belief that loan spreads and overall yields have bottomed and further reductions can only be achieved on account of a further reduction of risk as a result of corporatisation, increase of size, public floatations and the like. The loss of state guarantees and the need for German banks to adapt to an environment without state support has meant that such banks will have higher borrowing costs. Consequently, German banks which have been the main competitors driving spreads lower, may need to adjust their spreads upwards or at a minimum maintain their margins, as there is no room for further reductions.

The rush for growth will continue for most Greek owners, thereby providing plenty of opportunity for banks to develop their loan portfolios alongside.

In addition to growth in the value of the Greek fleet, new “niche” players have entered that give the market a much needed variety and depth. Whereas loan volumes are expected to grow at a more moderate pace, the number of banks participating in Greek ship finance is not expected to change significantly. The reason being that all banks currently engaged with Greek ship finance are pleased with their results and a reduction in numbers will arise only as a result of mergers and acquisitions. However, new large banks, primarily European along with some Far Eastern, are expected to enter the market, as are some smaller “niche” banks aiming their services towards the small to medium owner.

It is expected that although the individuality and character of Greek owners and Greek ship finance will remain, there will be a shift towards carrying out ship finance in the same manner as in other ship finance centres such as Germany and Scandinavia, where financial engineering and structuring are more prominent.

The key to all the above developments in the short term is that international trade continue to grow over the next few years. This is vital as newbuildings come up for delivery, since a pronounced and prolonged market fall at this stage of the development of Greek shipping and Greek ship finance may catch a number of owners and banks in a rather overextended position. Whilst the warning signs are evident, it is correct to state that most banks and owners operating in the Greek market remain confident of the future of the Greek ship finance industry.

Korean Shipbuilding Productivity

By Worldyards

Editor’s Note: In April we considered how banks and owners could minimize delays in newbuilding construction and be sure both parties received maximum value for their investment. Now we look at a reverse phenomena: how strong demand and high prices have driven some yards to increase efficiency and therefore capacity above and beyond what had been ordered.

August news of a tenth drydock at Hyundai Heavy’s Ulsan shipyard (640m X 92m, January 2009 completion) underlines the acceleration of capacity of South Korean shipbuilders. It is clear that we are in supply super cycle with a doubling of capacity through to 2010. Demand has been vigorous for most of 2007 in the bulk arena while a surge of mega containership contracting has added an unexpected dimension to the newbuilding juggernaut.

Unlike the multi-pronged demand of last year, with owners chasing bulkers, tankers, containers and LNG, this summer’s hunger in the newbuilding market was clearly for big containerships. Continue Reading